[ad_1]

Can a GoPro do astrophotography? Common sense says an action camera primarily designed for filming high-octane videos of bike rides and TikTok shorts isn’t going to be much use when the sun goes down. However, just as smartphone cameras now use low-noise sensors to fuel impressive ‘night modes’ so the GoPro is, with every iteration, getting better at coping with low light and even complete darkness.

‘Night Photo’ and ‘Night Lapse’ have been available on the GoPro for a few years, but new to the GoPro Hero 11 Black and GoPro Hero 11 Black Mini are three new night effects modes – ‘Star Trails’, ‘Light Painting’ and ‘Vehicle Light Trails’. They join ‘Night Photo’ (only on the Go Pro Hero 11 Black) and ‘Night Lapse’ to create a generous niche of night effects.

Here’s everything you need to know about three modes we think astrophotographers will be interested in – Star Trails, Night Lapse and Night Photo.

Read more: Best GoPro cameras in 2023

How the GoPro works at night

Both new GoPros have a fast 12mm wide-angle lens that is capable of f2.8 aperture, so lets plenty of light in at night. Just as important is a larger 1/1.9”/6.4×5.6mm CMOS sensor, which allows for images at night up to ISO 1600 (which is nowhere near what the best cameras for astrophotography can manage, but is just enough to impress). GoPro uses this strictly for photos, not video, when used at night. To create Star Trail and Night Lapse files it therefore takes a series of long exposure photos before splicing them together into one video file that’s viewable in seconds. It essentially automates a process that, otherwise, can take a bit of time in post-processing. Traditional startrail images are typically one still image, but the GoPro produces an animation that, arguably, looks much better on social media.

Read more: Astrophotography tips

GoPro’s new ‘night modes’: Star Trails

Above: Startrail video from a light-polluted city (30 secs exposures for 5 hours, ISO 800) with GoPro Hero11 Black Mini

It’s a classic of the genre – a long exposure image taken over two or more hours that shows how stars move across the night sky. Point your camera at Polaris, the North Star, and you’ll get concentric circles that show the rotation of Earth. Given that it’s something that astrophotographers like to produce using a second camera pointing north while they get on with more technical Milky Way shots while facing south, the presence of a star trails mode on the new GoPro is hugely welcome.

On the GoPro Hero 11 Black and Mini, the settings for Star Trails images can be tweaked, but not as much as we’d like. The animation can be changed from short to long, the resolution set to between 4K and 5.3K and in either widescreen or 4:3. Crucially, the shutter can be left open for between just 0.5 seconds and 30 seconds. It’s the latter you really want to produce star trails, though if you’re in a light-polluted city a shorter exposure is helpful to reduce ambient light, Sadly, the increments are annoyingly wide – there’s a jump from 10 seconds to 30 seconds. A 20-second setting would be very useful here. The ISO can be set from ISO100 to ISO1600, though the default – ISO800 – is a good choice in most scenarios. There’s no option to tweak the color balance, which is stuck at 3200K, while there’s also no way of setting exposure compensation – which, again, would be helpful for combatting light pollution. Either way, you need a clear sky to produce a startrail, otherwise all you’ll see are clouds sweeping across.

Read more: How to capture star trails

GoPro’s new ‘night modes’: Night Lapse and Night Photo

Above: Night Lapse video of cloudy night

Night Lapse video are time-lapse videos captured in the dark. While the GoPro Hero 11 Black adds Night Photo, the GoPro Hero 11 Black Mini doesn’t include it, though screengrabs can be pulled from both 4K (8MP) and 5.3K (16MP) videos. Night Lapse videos can also be created in 1080p and 2.7K resolution and the lens set to either wide or linear. There are generally more options than for the Star Trail mode, such as a wider choice of shutter speeds (including 15 and 20 seconds), an exposure compensation mode (two stops on either side), and the full gamut of color temperatures. However, it only works up to ISO 800.

Read more: How to improve your astrophotography: tips, tricks and techniques

What I loved about using the GoPro at night

It’s totally set and forget. Using either the touchscreen on the GoPro Hero 11 Black, the Quik app on the GoPro Hero 11 Mini or the Quik app on either it’s so easy to choose the mode you want, put the camera in place then begin the shot. Given that it’s very easy to crop the resulting videos you can even set the camera rolling while it’s in your hand and then go position it. Although the WiFI network the GoPro spits out for using with the Quik app is limited in size, it doesn’t really matter if a connection is lost because the GoPro will continue with its shot until the battery runs down. Shortly before that happens the file is saved to the micro SD card for easy retrieval later. We left a GoPro outside all night to capture a five-hour star trail while it was attached a portable battery, with no issues – it worked all night.

After the shot is complete it’s very quick to appear in the Quik app as a low-resolution preview, easy to edit and simple to upload to YouTube.

The quality of star trails are easily good enough for most astrophotographers, so this new GoPro is particularly well suited to those who want to cut down on kit and just throw a GoPro and a small tripod into their camera backpack, setting it up in a dark corner facing north while they get on other, more complex compositions.

Read: The best tripods right now

What we hated about using the GoPro at night

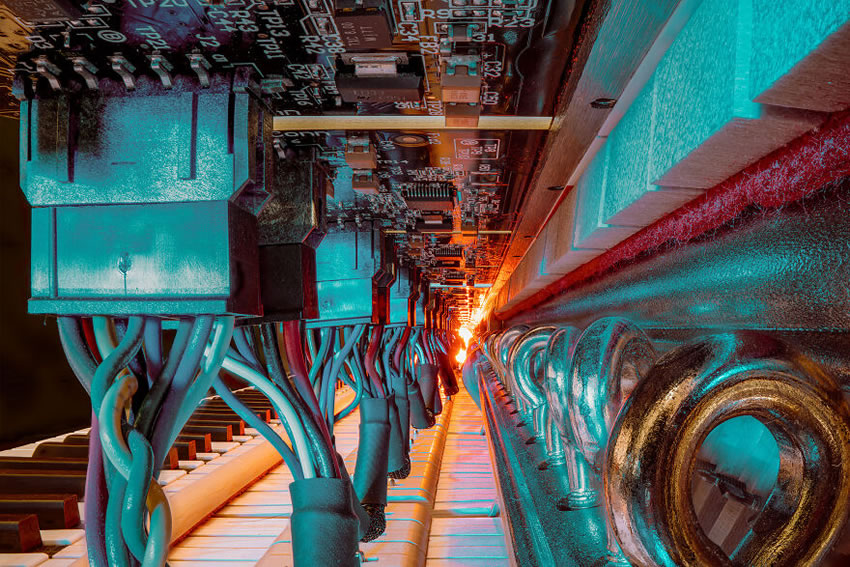

Above: Night Lapse video of a starry night

Night Lapse videos are poor on clear nights. While the Star Trail mode works really well and stars look bright, that’s not the case with Night Lapse videos, during which stars are virtually invisible in urban conditions. You’re not going to want to download still images from Night Lapse videos. The only scenario in which Night Lapse impressed during our test was when clouds were sweeping across a location, which in a city is always uplit by light pollution.

Although Star Trails impressed, it would be helpful if individual frames could be removed. That’s the only way to combat airplanes, satellites and neighbor’s lights being switched on mid-trail becoming part of the star trail file.

What the GoPro Hero 11 Black Mini lacks is a preview screen for its night modes so it’s tricky to frame a shot, though given the wide field of view it’s not a serious issue. The biggest problem with using a GoPro for night work is its battery, which only just about lasts long enough for a star trail. Given that the resulting video shows a star trail developing over time, about four hours is usually enough to impress – not the two hours you’re going to get from either GoPro. The GoPro Hero 11 Black has a 1,720mAh Enduro battery that can be replaced, which while an advantage for many users isn’t much good for astrophotographers. The GoPro Hero 11 Black has a built-in 1,500mAh Enduro battery that can’t be replaced. Crucially, both can be recharged using a portable battery. Find a waterproof model and a USB-C cable long enough to reach the camera (if using a full-size tripod) and consider getting GoPro’s USB pass-through door (opens in new tab).

Read more: Best lenses for astrophotography

Verdict

As far as astrophotography goes on the new GoPro models, we were impressed only with the Star Trails mode. It’s excellent, quickly producing a good-looking animation, with 16MP stills downloadable. It’s capable of going all night if left attached to a portable battery. Not so Night Lapse, which only impresses if you want to shoot a timelapse of clouds.

If ultimate space-saving when doing astrophotography is important then consider the GoPro Hero 11 Black Mini, which has three distinct advantages over the flagship model when it comes to astrophotography: a 13% smaller footprint so easier to get in a busy camera bag, a built-in battery can be topped-up using a portable power bank and a USB-C cable, and two sets of folding fingers for mounting – so it can be more easily attached to an existing tripod being used with a DSLR or mirrorless camera.

The brightness of stars will depend on the quality of darkness in your location – so check a light pollution map and head to a dark spot, or find a Dark Sky Place, for best results – but if you want a set-and-forget way to take star trails the GoPro Hero 11 Black and GoPro Hero 11 Black Mini fit the bill.

[ad_2]