[ad_1]

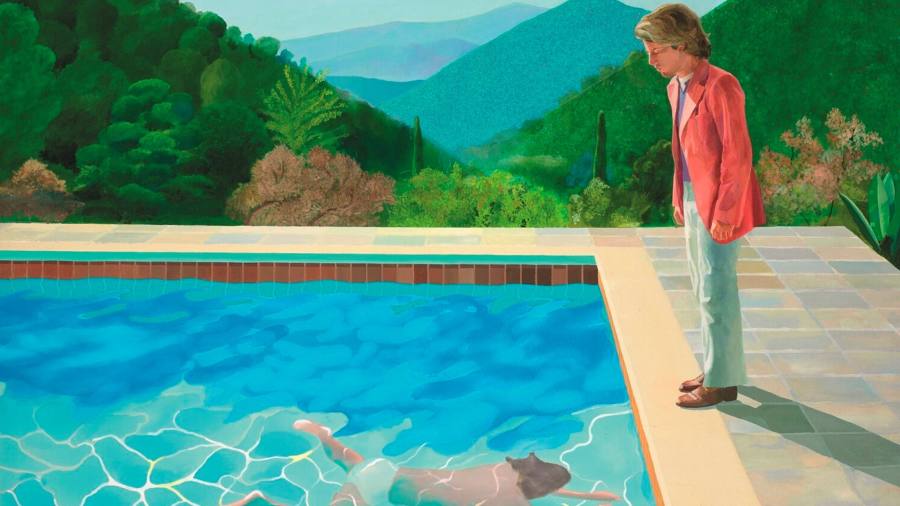

David Hockney’s limpid stretch of radiant blue broken by tangled lines, “Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)”, scintillates across the central gallery in Capturing the Moment, the new exhibition at Tate Modern in London about the relationship between painting and photography. As his source, Hockney took numerous snapshots of the pool (in St Tropez) and the downward-gazing observer (his former lover Peter Schlesinger, in Kensington Gardens). Collaging the disparate images, the painting captures a joyous instant of sun hitting water and, in a breath, a glance, complexities of desire, loss, regret. Hockney spent more than 200 hours depicting what appears as this single decisive moment — a virtuoso imitation in paint of a photograph that never was.

Taiwanese entrepreneur Pierre Chen bought the painting for $90mn in 2018 — breaking the record for a living artist. It returns to the UK as one of a score of stunners from his Yageo Foundation, the only lender to the show (everything else comes from Tate’s collection). Chen’s paintings range from Picasso’s brutal-delicate “Buste de Femme” (1938), face fractured yet somehow jaunty beneath a comic feathered hat, a work never before shown in Britain, to Peter Doig’s cinematographic fluorescent green “Canoe Lake” (1997-98), among his earliest, eeriest pieces based on an uncanny scene from the horror movie Friday the 13th.

Tate’s theme is laid out in a Picasso quotation in the opening gallery: “Photography is capable of liberating painting from all literature, from the anecdote, even from the subject. So shouldn’t painters profit from the newly acquired liberty to do other things?” This is modern art’s foundational narrative — painting set free from the documentary impulse — and a hopelessly broad, well-worn premise for an exhibition: anything at all from Tate’s collection would fit it. The surprise and delight of the Yageo loans alone make a visit worthwhile.

Chen was a teenager when he launched his electronics business in 1977, and he began buying art around the same time: ironically enough, a fortune made from mechanisation — his company supplies mobile phone and computer components — allowed him to amass a supreme collection of handmade works.

He also takes risks. First star here is Picasso’s disguised self-portrait of wartime claustrophobia “The Sailor” (1943) — club-like fist, anguished expression, skewed perspective — which Chen bought after it was punctured by a metal rod ahead of its expected sale at Christie’s in 2018. Another is Francis Bacon’s “Study for a Pope VI”, last of six depictions following Velázquez in an important 1961 series. In the others, the pontiff is upright, gesturing, desperately trapped; here he slumps, head tilted as if he has given up and fallen asleep. His surplice dissolves into dripping white paint on raw canvas. Flamboyantly offhand — or just unfinished? — it’s a potent emblem of pathos and defeat.

“The Sailor” has not been in the UK since Tate’s 1945-46 Picasso show, and the “Pope” not since the museum’s 1962 Bacon retrospective, for which the series was made. Fabulous, historic loans, then, to demonstrate how 20th-century figurative painting survived by becoming ever more sensational, exaggerated, responding to harrowing times. “The age demanded an image/of its accelerated grimace,” Ezra Pound wrote.

From Taiwan there’s Bacon’s “Three Studies for Portrait of Lucian Freud”, also not seen for decades — head shattered, then rebuilt to shudder in and out of deep walls of red paint, one hand raised in defence against the mangling — alongside Tate’s early Freuds. A highlight is the menacing/vulnerable “Boy Smoking” (1950), a young criminal with furrowed brow, too-wide eyes, too-thick lips, cigarette casting a livid shadow down his chin. It shows Freud’s life-long quest “to move the senses by giving an intensification of reality”, outdoing the camera’s objectivity with his own mix of monstrosity and indifference.

Freud stuck doggedly to it while his contemporaries in the 1960s started pulling photographs directly into painting. Robert Rauschenberg (“Almanac”, a flux of everyday images over-scrawled in white paint) and Andy Warhol (“Double Marlon”, Brando as gang leader in The Wild One) screen-printed photographs and movie stills, appropriating their banality or glamour.

Gerhard Richter copied old snapshots, blurring them into uncertainty by grisaille paint. The Yageo’s “Aunt Marianne” is based on a sweet photo of baby Richter held by his smiling aunt — whom the Nazis would diagnose as schizophrenic and leave to starve to death in a psychiatric institution. Richter questions layers of collective denial in post-Nazi Germany. The camera can lie, his paintings assert, and no image is immune from manipulation for political purposes.

German photographers playing on ambivalence between the camera’s neutrality and austere formalist composition, derived from painting, continue the thread: Andreas Gursky’s panoramas of crowds and apartment blocks “May Day IV” and “Paris, Montparnasse”, Thomas Struth’s and Candida Höfer’s geometric, precise museum and library interiors. These comprise half the small photography section — scanty for a show subtitled A Journey Through Painting and Photography.

Finally come recent Tate acquisitions, tremendously varied in quality. Heaven help “painting in the digital age” if its future is as bloodless and pointless as Laura Owens’ “Photoshop marks” layered on grids (“Untitled”, 2012) and Christina Quarles’s “transforming random marks into stretched human figures” (“Casually Cruel”, 2018), explained as gender politics: “Whereas gestural painting is traditionally associated with heroic, masculine actions, these artists use digital rendering to create carefully controlled gestures.”

Saviours are two major pieces by the freshest and most sought-after names, entering the collection thanks to Tate’s Africa Acquisition Fund. Michael Armitage’s “The Promised Land”, dreamy fantasia turned terror scenario, bodies metamorphosing under tear gas, references news images of a fatal protest in Kenya. Seeking “a visual metaphor for the multiple sources of influence on people’s experiences”, Njideka Akunyili Crosby collages kaleidoscope-bright photographic fragments representing Nigerian culture — hip-hop musician Nneka, novelist Chinua Achebe, Nigeria Airways — in the engrossing domestic scenes “Predecessors”. Both assimilate photographs into vibrantly contemporary works celebrating painterly possibility.

Several elements here could have made an intelligently focused independent show — the Yageo collection itself; 21st-century painters’ evolving engagement with photography — rather than the mere glimmers of interest offered in this lazy apology for an exhibition.

To January 28 2024, tate.org.uk

[ad_2]