[ad_1]

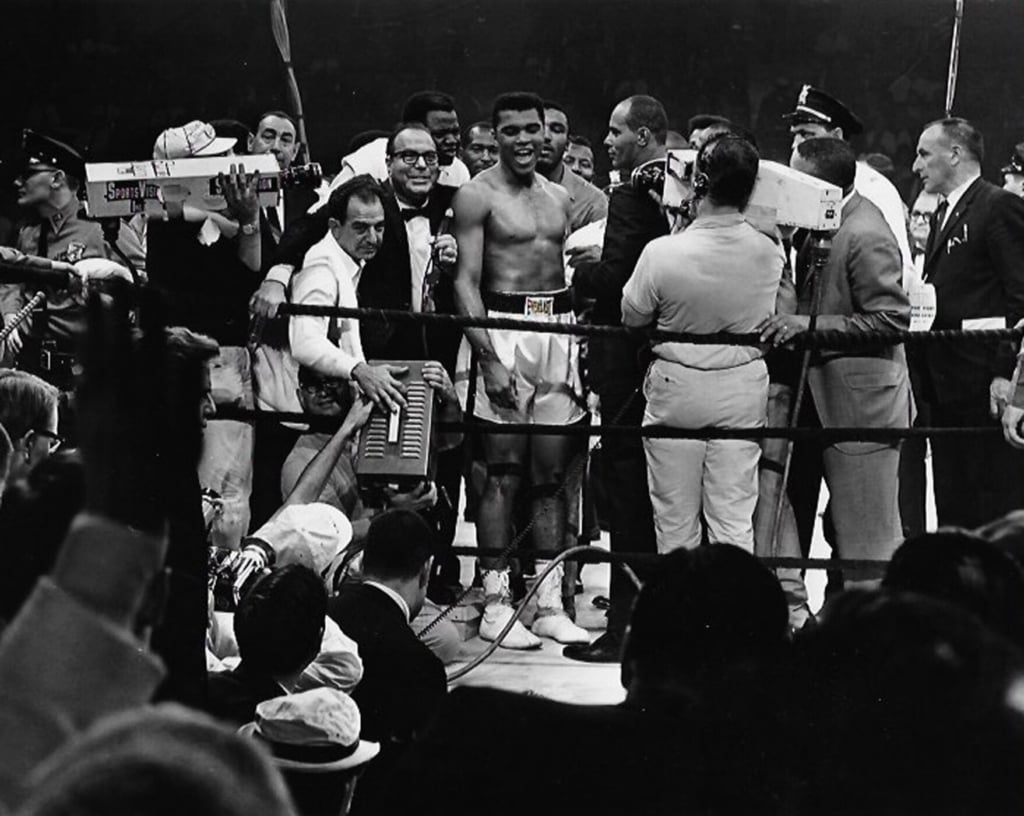

Donald Johnson was there, camera in hand, as presidential candidate John F. Kennedy greeted a small boy during a campaign stop in Portland in 1960. A year later, he captured the crumbling Union Station clock tower as the ornate granite building was razed in the name of urban renewal. And in 1965, he was in the arena as Muhammad Ali knocked out Sonny Liston with his so-called “phantom punch” in the first round of their match in Lewiston.

During his time as a staff photographer for the Portland Press Herald, Johnson documented notable events in Maine history. But he also captured smaller moments that offer a compelling glimpse of life in Portland in the 1950s and 1960s.

Johnson, a self-taught photographer with a fondness for nature and the working waterfront, died Nov. 1. He was 92.

In September 1960, Senator John F. Kennedy campaigned in Maine before speaking at the Portland Stadium.

In September 1960, Senator John F. Kennedy campaigned in Maine before speaking at the Portland Stadium.

Union Station demolition

During his career as a newspaper photographer, and later as a freelancer, Johnson had a knack for putting people at ease and making images that were timely and memorable, said John McCatherin, a former journalist and longtime friend who worked with Johnson on projects starting in the 1960s.

“He had a sense that I don’t think all photographers had, to know the moment,” McCatherin said.

Johnson was raised during the Depression in South Portland, where his father was a carpenter and his mother was a homemaker. He was the middle of seven children in a family with very little money. He developed an interest in photography when he was young and somehow saved up to buy a Kodak Brownie. He built a darkroom in his parents’ house so he could develop his own film.

“I don’t think he remembered a time when he wasn’t taking pictures,” said his son, Keith Johnson.

The 138-foot-tall clock tower at Portland’s Union Station crumbles to the ground as the station is demolished in 1961 to make way for a strip mall.

At the famous 1965 Lewiston fight, heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali defeated Sonny Liston in the first round. It was the first time Muhammad Ali fought under this name, but local newspapers still referred to him as Cassius Clay.

The heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali defeated Sonny Liston in the first round of their title fight in Lewiston, on May 25, 1965.

After graduating from South Portland High School in 1948, Johnson served in the Marine Corps for two years before returning to Maine to focus on his photography career.

In 1950, he was hired as a staff photographer at Guy Gannett Publishing, then the publisher of the Portland Press Herald, Maine Sunday Telegram and Evening Express. He was just 20 years old. He worked at the newspaper until 1972, then did freelance work until his retirement at age 80. His family says he never stopped taking photos.

The 1966 Maine gubernatorial election pitted Kenneth M. Curtis against Republican Governor John Reed, who was seeking a second term. At a rally in October 1966, Curtis, left, with Sen. Edmund Muskie and Congressman William Hathaway listen to Sen. Robert Kennedy at a campaign rally in Portland.

Sen. Robert Kennedy in Portland in September 1966.

During his career, Johnson documented the last steam engine to leave Maine, the state’s last log drive and the clearing of the site that would become the Cumberland County Civic Center. He photographed Mainers at work and at play, campaign events and boats on the waterfront. He made portraits of poet Carl Sandburg strumming a guitar in 1959, and of author E.B. White behind a typewriter in 1969.

Bette Davis, left, Carl Sandburg and Gary Merrill, Davis’s husband in 1959. Davis starred in “The World of Carl Sandburg,” a stage presentation of selections from Sandburg’s poetry and prose, and the show premiered in Portland.

Carl Sandburg, 1959

Johnson received national attention and an award for a photo he took in February 1956 of a father and son embracing as their family farm burned down. He loved taking photos of nature and Portland after snowstorms.

He married in 1954 and he and his wife, Jane, raised their three children in Westbrook. After the couple divorced in 1980, he moved to Portland. He spent his last 40 years with his partner, Cheryl Cook. They lived together in Otisfield until Johnson moved to the veterans’ home in South Paris a year and a half ago.

When his children were young, Johnson would sometimes bring them along on assignments. Jill Detmer remembers her father waking her in what felt like the middle of the night to go down to the waterfront, where they would ride on tugboats. When she was around 10, she went with him and a reporter on the last passenger train trip from Maine to Montreal. They rode home in the caboose of a freight train.

Donald Johnson, 1962

During those outings, Detmer saw how easily her father connected with people.

“When he was getting a photo together, he wasn’t demanding,” she said. “He knew what he wanted and he knew how to get people to do what he wanted.”

His son remembers tagging along with his father to the Press Herald building on Congress Street. Johnson was always on call and never hesitated to chase after a fire truck so he wouldn’t miss a shot, even if he had other plans.

“He lived photography first,” Keith Johnson said. “He had to document everything.”

Folk singer and social activist Pete Seeger plays before the launch of the sloop Clearwater in South Bristol in 1969. In 2004, the Clearwater was placed on the National Register of Historic Places for its groundbreaking role in the environmental movement.

In despair over the pollution of his beloved Hudson River, folk music legend Pete Seeger came up with a plan to raise money and awareness by building a boat like the old 19th-century sloops that sailed the river. The sloop Clearwater, in the back center of photo, launched in South Bristol on May 17, 1969, making its maiden voyage from the Harvey Gamage Shipyard to the South Street Seaport in New York City – and eventually on to the Hudson River.

Sen. Margaret Chase Smith, R-Maine, and Sen. Robert Dole, R-Kansas, praise the Nixon administration at a news conference in Portland on May 15, 1971. Dole, chairman of the Republican National Committee, was in Maine to speak at a fundraising dinner for Smith.

McCatherin, who had been a reporter at the Kennebec Journal and Associated Press, hired Johnson for freelance assignments when he edited the company publication for New England Telephone. Johnson’s photos were always terrific, he said. McCatherin’s favorite – a spectacular color photograph of the sun rising over Cadillac Mountain taken from a plane – still hangs in his office.

During the holiday season, McCatherin and Johnson traveled the state by car as Johnson took photographs of people, places and equipment for the telephone company to use throughout the year. They would gab all the way from Portland to Madawaska and back, McCatherin said.

“It was always a treat when we’d finish up the trip and a few days later I’d get proof sheets from Don,” he said. “I would sit there and smile because it was always great stuff.”

After several of his close friends died suddenly in the 1970s, Johnston took up running. He loved running, even in winter, and kept it up until he was 80, his daughter said. When she lived in San Francisco, he visited each year so they could run the 7.4-mile Bay to Breakers race together.

President John F. Kennedy, the 35th president, in Orono, where he received an honorary degree.

President John F. Kennedy received the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws at the University of Maine, Orono on Oct. 19, 1963, a month before he was assassinated in Dallas.

Jill Detmer and her father, Donald Johnson, in 1995 at the Bay to Breakers race in San Francisco.

Johnson loved to be outside and would spend hours waiting for the perfect nature shot, unbothered by the weather conditions. He climbed Mount Katahdin, went to Gulf Hagas and traveled Down East, camera in hand. He and his son would go fishing, but Johnson was always more interested in taking photos than catching fish.

“He never went anywhere without a camera, ever,” Keith Johnson said.

Johnson bought a camp on Little Sebago in 1971 and loved spending time there with his family. He visited for the last time about 10 days before he died and he was happy to be back, his son said.

“The older he got, the more he valued time,” he said. “He didn’t want anyone to be unhappy. He was always looking on the bright side of life.”

One of Maine’s last log drives

One of Maine’s last log drives

Throughout his life, Johnson was curious about the people and world around him. It wasn’t uncommon for him to wander off during a hike because he he had spotted something he wanted to photograph. When he and his daughter went to Iceland, Johnson insisted they get off the main roads to really explore the country.

He also was curious about the lives of his three children, six grandchildren and three great-grandchildren, Detmer said.

“He was very good at listening and asked incredible questions,” she said. “I felt very important to him.”

When Johnson moved into the nursing home, he wasn’t allowed to have a camera with him. It drove him crazy to be without one, but his children made sure to have a camera ready to use on trips to camp or other outings.

“He had to be a photographer,” his son said. “That was just in his blood.”

« Previous

Next »

Related Stories

[ad_2]

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you’ve submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.