[ad_1]

Technological advances have helped Cruz and other citizen scientists document celestial objects millions of light years away from Earth.

For the last 25 years, capturing ancient light has been Isaac Cruz’s favorite pastime.

As a seasoned astrophotographer—someone who delights in taking pictures of objects in space—he’s created hundreds of images of comets, planets, galaxies and nebulae: celestial objects whose light can take millions of years to reach Earth. It’sa serious, time-consuming hobby, but Cruz enjoys the privilege of adding his own twist to humanity’s understanding of the universe.

“There are so few people [who] have the opportunity to actually sing the wonders that are in the night sky,” Cruz says. “My joy is to share that.”

Like many in Columbus’ tight-knit astronomy community, Cruz began his astrophotography career with a simple DSLR camera, collecting photos of the night sky by pointing the device through the eyepiece of a telescope. Yet those early attempts pale in comparison to what he and others in the field can create today.

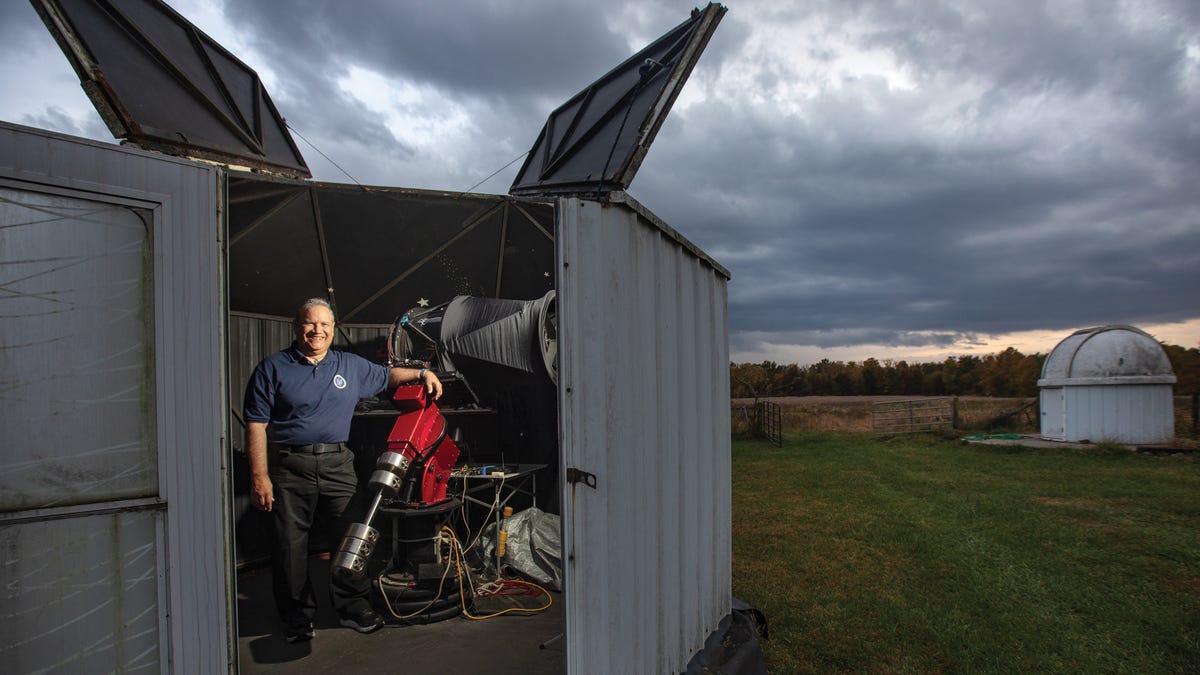

As technology and astronomy advanced, Cruz’s simple setup evolved into a complex observatory, a solitary glow-in-the-dark outpost set on a private farm in Knox County, rife with equipment like high-resolution cameras and various kinds of imaging processing software. But stars keep odd hours, and to get the perfect shot, Cruz often leaves his home in Reynoldsburg at dusk, returning to his bed only when dawn peeks sleepily over the tired countryside. Considering that humans are unable to see certain kinds of light until processed into visible color, combined with a celestial object’s fickle transit across the sky, some photos have taken anywhere from a few weeks to a few months to construct; others have taken years.

“The image is done when you’re happy with the image,” Cruz says. “In other words, it’s your interpretation of what you actually get.”

More recently, his work has gained acclaim in several media outlets, including popular astronomy magazines like Sky & Telescope. Now a retired electrical engineer and a former president of the Columbus Astronomical Society, Cruz imparts his passions to the next generation by mentoring amateur astrophotographers on what instruments might help them perform better and giving them advice on what Cruz describes as “coaxing light out of the dark.”

Though creating professional-grade astrophotography photos can be more technical than the average person might expect, starting small is easy to do. All a beginner needs is a camera, an open area to view the unobstructed sky and a discerning eye for the beauty of the cosmos. “To realize that there are billions of galaxies in the universe is fascinating to the young, and, sometimes, to the not so young, as well,” Cruz says. “To be able to see those objects, it actually brings it home.”

But astrophotography isn’t only about crafting pretty pictures. It can also help record scientific data. Cruz notes that he has succeeded twice in helping to detect exoplanets—worlds that orbit stars outside our solar system.

When astrophotography emerged in the early 1800s, people began taking photos of the sky to track celestial objects, a factor that contributed to numerous scientific discoveries. For the first time in history, a wealth of astronomical data could be both documented for later perusal and cherished as mementos for later generations. Such capabilities have long held a strange mystique for amateur and professional astronomers, but over the last two decades, Cruz says interest in astrophotography has exploded, with entire websites being dedicated to the posting and sharing of these unearthly images. The subfield’s nebulous, otherworldly aesthetic has even influenced how astronomers choose and make visual adjustments to publicly released space photos from missions like the Hubble Space Telescope or the James Webb Space Telescope.

Bryan Simpson, president of the Cincinnati Astronomical Society, attributes the boom to social media and the advent of better digital technologies and specialized cameras. And despite the worry that this ease of access might turn astrophotography into a passing fad as internet-goers are every day inundated with new fascinations, Simpson notes that the field does have an immense influence on pulling all kinds of people into astronomy’s orbit.

“Astronomy being one of the most accessible of all of the sciences, [it] is a great entry point for people,” he says. “Because let’s face it, most people aren’t going to go buy a microscope to look at germs and bacteria. But they do go outside at night, and they look up.”

This story is from the December 2022 issue of Columbus Monthly.

[ad_2]